Editor: 何舫 Time: 2019-09-09 Number of visits :453

The Secret of Chinese Economic Development: Socialist Core Value

An Observation during the Practice in School of Marxism in Zhejiang University

“China: Economic development and core values”

By Francisco J. Lucero Bravo

Sociologist – Master in Politics and Government, University of Concepción

fjlucerob@gmail.com

Economic development

On the day that the thriving Huawei phone company announces that it will launch its own operating system, in response to Google's measure of not allowing its devices to access Android updates, it is the time when we can draw some interesting lessons about the good economic moment that China lives, paying attention to some cultural, social aspects and its recent history.

The announcement of Huawei is framed in the context of the trade war that hold the United States and China where Trump’s administration has puted on restrictive measures on Chinese products accusing, among other reasons, a significant deficit in its balance of payments with that country. That is why the Chinese response to launch its own operating system acquires greater spectacularity, given that it is interpreted as a counterattack that, in order to have been carried out and meet the stated deadlines, requires considerable prior time having worked on the design of said operating system. It's like the Chinese company would have made some custom moves and will find the window of opportunity to make the announcement. We will not discuss here if this strategy manages to compensate for the losses that Google's measure could mean (with greater customer loyalty and the potential attraction of new stakeholders in a product that is increasingly autonomous and sophisticated) since this example we have brought it up just to raise the course of this work and open the discussion.

To know some of the reasons that explain the vertiginous economic development of China in the last decades, we must first give some data that give account of what we are talking about:

In 25 years (1990 - 2015) multiplied its GDP per capita by 10 and its global GDP multiplied by 30 (Jao, Jun, Pentland et al, 2017); for more than a decade it grew by over 10% so that in 2012 it will only drop to 7.8% and reach 6.6 in 2018 (World Bank) ; in terms of innovation, it occupies the 17th place of innovation in the Global Innovation Index 2018 (GII 2018).

For Jao, Jun, Pentland et al (2017), the main reason for this historic record exhibited by China was its ability to manufacture sophisticated products that were above its income level. In turn, this was due to their ability to learn while economic literature has vast evidence of the importance that the processes of incorporating knowledge and skills in networks of individuals have for economic development. The authors in question focused on relieving the displacement of the Chinese economy according to inter-industrial and inter-regional learning (between provinces in this case) with special emphasis on economic complexity factors related to ubiquity and diversity of its productive structure (Hausmann and Hidalgo, 2007).

Since the economic restructuring commanded in 1978 by Deng Xiaoping, China promotes what it calls a “socialism with Chinese characteristics” where the State controls strategic sectors of the economy but allows private property to be extended as it had never done since the last abdication represents the Qing dynasty, Pu Yi who abdicates in 1912. Chinese socialism, led by the Chinese Communist Party, with Xiaoping at the helm, seeks to develop the productive forces that until then were in marked delay with respect to foreign economies. This is why learning plays a key role in this regard and the economic reform challenges that are sought to be faced require that what is happening in the international market be observed. However, this attitude to observe and learn from what happens in other attitudes is not recent. China imported Buddhism, then Marxism and now would do so with capitalism, although in each of these cultural assimilations it made adaptations from its own social, cultural, traditional and historical heritage. Now it was appropriate to do the same with technological advances and human and creative potential was ample, as the contemporary indicators reviewed above would demonstrate. We can say, then, China accepts a challenge of modernization and diversification of its productive structure, opening and controlled liberalization of its market and partial privatization of its industry whose successful results are obvious.

This challenge of learning about the technological ventures of the West goes hand in hand with the adequate development of the productive forces that until then had been neglected. This required following two main courses: the strengthening and diversification of the domestic industry; and the opening to the global market through a massive influx of foreign capital. It is in this sense that Deng Xiaoping in the early 80's establishes the first Special Economic Zone in Shenzhen, which will be followed by others to replicate his model in Zhuhai, Shantou and Fujian. Venture capital industries were formed that financed much of the infrastructure of these special economic zones. This process began the creation of products with higher added value and sophistication, as also laid the foundation for the development of multinational companies who returned to invest in China's booming economy that opened the world (Kunal Sinha, 2008).

Figure 1: “China's productive structure in 1978”

Source: Source: Economic Complexity Observatory ( https://atlas.media.mit.edu ). The data correspond to the year 2017.

This is how Figure 1 indicates, it is observed that in the year of Xiaoping's reform, China's productive structure was mainly defined by the textile industry that represented 29% of exports, followed by the oil and hydrocarbons sector with a 15% and agriculture with 14.5%. At that time, the machinery and electronic products sector barely represented 2%.

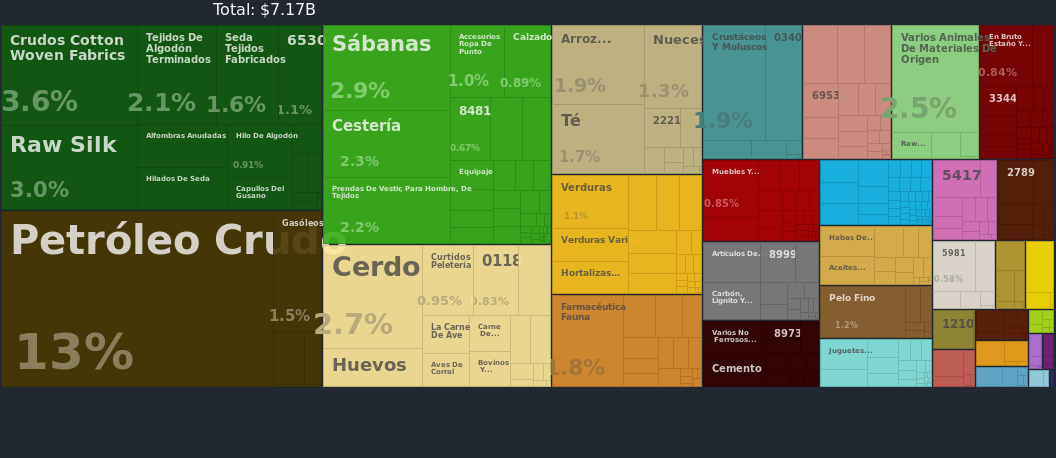

Figure 2: “ China's productive structure in 2017”

Source: Source: Economic Complexity Observatory ( https://atlas.media.mit.edu ). The data correspond to the year 2017.

Then, in Figure 1, we see how China's productive structure to 2017 changes radically and is mainly constituted by the sector associated with machinery and microelectronics that exceeds 50% of its export volume. This sector includes a wide range that goes from broadcasting equipment, integrated circuits, computers and telephones to motors and electric batteries. It is followed by a textile sector with 9.9%, diverse with 7.2% and metals with 7.1%.

This very radical qualitative leap, of course, responds in large part to a successful adaptation to the demand for labor and investment opportunities that economic openness meant. But unlike other structural reforms such as those experienced by Latin American countries in the 80's, economic openness was not accompanied by a deregulation of strategic sectors, but on the contrary, control over development strategy was maintained with a strong component local and regional that prioritizes certain sectors. As Piketty points out, China has always regulated and applied controls to its capitals, ignoring the recommendations of international organizations such as the OECD, the IMF and the World Bank (Piketty, 2013, p. 599) .

Cultural values and political project

From a political point of view, economic openness was a way of solving the governance problems that the Chinese government was having. The freedoms claimed by citizens at the socio-political level could be channeled through the market through access to new goods and services from abroad. The success of this process would bring prosperity, as one of the most important objectives that this new country project visualized. In this way it is considered that the State is oriented towards a good government pursuing the general interest and the market provides governance for the development of a dignified, prosperous and free life.

In a way, the international opening of the Chinese economy would be conducted with certain guards (as expressed in the previous section), which implies that there will be an ideological framework that will protect the opening process. The political will seek the development of the economic from a certain cultural framework. This cultural framework will be given by a set of values that are exalted and promoted by the Chinese government. These values respond -as in all cases of building a nation-state - to a select review of the historical development of a civilization.

First, let's start by clarifying what we understand by values. For Graeber (2001), values are the way in which people represent the importance of their own actions to themselves. In other words, the meaning framework of their actions. Then, Graeber will propose a new concept - more useful for the purposes of this work - which will be that of form-values, which not only represents the action but also makes it desirable. The values-forms are understood as a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy , in which people usually follow their own beliefs, convictions and values that when carried out in practice are confirmed by themselves. Some of the criticisms that this approach receives, for example those made by Claudia Strauss, point to how it is possible for these cultural messages to be incorporated into people's cognitive and referential systems; What is the same, how values become desirable in the first place. The provisional answer that could be found in Durkheim would be that “collective effervescence” is not only about rites and customs, but also about the influence of reference models and encounters between people with myths and narratives (Robbins and Sommerschuh, 2016, p. 8 ) .

So, understanding that values (or form-values) are a reference system that guides the action and makes it desirable (with the reservations expressed above) it is time that we realize some of the values present in Chinese culture that can explain in part, the successful economic development process they have had during the last decades. First, we have the values of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) with its more than 89 million members, which are: loyalty, collectivism, discipline and hard work. While the last two (discipline and hard work) are clearly functional to an economic development model that seeks to focus on the free development of productive forces, the first (loyalty and collectivism) go hand in hand with the idea of maintaining and long-term project, therefore provide certain stability to the chosen techno-scientific and techno-economic regimes and trajectories.

In a political regime where the government is limited to the administration and management of state affairs (solution making), while decision making belongs to the CCP , the constitution plays a crucial role in the conduct of the market. This is why the values associated with the productivity of the workforce (discipline and hard work), such as those associated with the stability of investment (loyalty and collectivism) must be articulated under a framework referring to the greater. The concept of harmony comes into play here, which finds strong roots in the philosophical foundations of Chinese culture. Already in what is known as the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC) the historian Shimo said that "everything comes in pairs", so that the development of things comes from conflict and contradictions (Han and Zhang, 2018, p. 66). Then, Confucian philosophy will also highlight the gregarious nature of people, where the human being can only live in groups where differences coexist; and Daoism will do the same with the idea of the balance between human being and nature. Harmony as a concept and value-form may be the most distinctive aspect of Chinese culture, rescued and exalted by its current political regime. This value allows us to speak of a Chinese interpretation of Marxism, where the material component, in the case of Marxism, guarantees a place in the productive process and explains the class struggle at the cultural level; in the Chinese case, it is the guarantor of opportunities toward prosperity and, therefore, of freedom and access that solves many of the contradictions rooted in the very identity of people. For the Chinese interpretation of Marxism, the important thing about the dialectical process of material history (Marx) and of ideas (Hegel) is synthesis, as a conciliatory stage, while in its Marxist version, the contradiction between thesis and antithesis as dynamic mecanism of history is mostly emphasized.

In this way, while harmony constitutes one of the core values in the culture, there are others prioritized by the Chinese Communist Party to form a list of 12 values grouped into three levels: national development, society and individual.

Figure 3 . “Values promoted by the CCP according to the levels: National development, society and individual”.

Source: Own elaboration based on Zhen and Zhang (2018)

Figure 3 shows the classification values prioritized by the CCP, where we see at the country's development level, harmony is articulated with civilization, prosperity and democracy to promote proper management of resources in the territory.

Harmony, in addition to playing a key role internally, is also one of the pillars of international policy implemented in 2013 by the current president Xi Jingping, called OBOR (“One belt, one road”) . This geopolitical strategy that seeks to revive the ancient “silk road” of the times of the Han dynasty (207 - 220 BC), tries to move from a low profile stance on the international stage to an active search for success and development of commercial and diplomatic relations of mutual benefit. From a point of view, it is sought to counterbalance the influence of the United States at a global level, aligning with a more balanced international system proposal, which adapts some principles that were already being proposed at the BRICS summits (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). In this sense, China tries to influence a global process in progress, from the potential influence that its increasing material capacity provides. This is because although it focuses initially on the Eurasian region (Asia and mainly Eastern Europe), its ambitions are finally global.

The pillars of the OBOR strategy are: political coordination, free trade, financial integration and ties between people. These pillars are framed in principles of mutual benefit and learning among the countries that comprise it. According to World Bank reports, there is no official and exact figure of the countries that make up the initiative, although their research has focused on 71 economies that group 35% of foreign direct investment (FDI) and 40% of the world export volume (World Bank, 2018) . In 2014, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was founded, which seeks to turn China into a new global financial center.

The impact of China's international geopolitical positioning commitment has been such that in 2017, the global magazine The Economist published the article: “What to do about China’s sharp power”, referring to the influence that China has achieved in the way of doing politics of some countries that have accused some degree of intervention, such as Australia, United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand. On the other hand, the recent entry of Italy into the Beijing’s initiative, which joins 15 other European countries of which 11 are members of the European Union, activates the alerts of the central block of the European Union (Germany and France). The above, in addition to the Commercial War that the United States currently holds with China, revitalizes the popular “Thucydides trap” originally applied to the Peloponnesian War (5th century BC), as the idea that the emergence of a new power creates a threat of loss of hegemonic power in the prevailing power, to the point where an armed conflict becomes imminent. China insists through its public statements that its international relations policy is of "mutual benefit and learning."

Returning, the values prioritized by the CCP, prosperity, civilization and democracy complement this approach based on harmony to guide state affairs. Prosperity is associated with economic and technological development, which in turn affects a potential better provision of goods and services to the inhabitants of a territory. Civilization, meanwhile, refers to the integration to rules and shared standards. Finally, democracy, as a regime of government based on collective deliberation, the representativeness of public decisions and powers, freedom of expression and association, among other aspects. Of these three values, we could identify the latter as the most debatable, given that the political system in China has a totalitarian bias, where a single political party concentrates power, only limited by its constitution.

The CCP has a central committee of around 200 members, of which 150 only alternate and 50 occupy permanent positions. The leaders of the CCP receive a salary from the government budget and the members of the party are more likely to access government positions. The presidential elections are held through delegates who meet in the government palace to renew their ranks, make changes to the constitution and choose who will lead the country for 5 years. However, there are prototypes of democratic institutions that intermingle with the centralized power of the CCP, in which we find the fact that some large cities have legislative power. Congresses are also held every five years, which last from one to two weeks and issues of territorial interest are reviewed. And at the level of counties and communities there are elections of local authorities with mechanisms of supervision and evaluation of their performance by the inhabitants.

With respect to the second level of Figure 3 related to society, where we find the values of freedom, equality, justice and the rule of law, it is important to focus on the first two. The concept of freedom in Chinese culture has a more collective and communitarian connotation than the idea of the West, which is more individual and personalized. In this sense, freedom will always be understood in relation to others, to a larger group to which it belongs. That is why freedom is part of the second level (society) and not of the last one (individual). In China, the balance between government and governance represents the main focus of attention considering its internal cultural diversity, both for multiethnic and geographical (urban-rural) reasons and mainly because it is a country of 1.3 billion inhabitants. This is why this idea of freedom under the rule of law does not come into direct conflict with the idea of equality, which does occur in Western societies. In addition, freedom understood as self-realization according to the principles that govern society is very close to the idea of the rule of law that is at the same level of analysis. We must also say that the freedom raised by the CCP, comes from a materialist interpretation (Marxist), where the State must be responsible for providing certain guarantees in the provision of certain services such as health, education, housing, among others, so that the development of Freedom is based on concrete actions and not abstract ideas. Restricted freedom, in this way, is based on the achievable above an idea of broad freedom that can be based on the possibility.

Then, the idea of equality is associated with the idea of dignity for all, so it is in perfect balance with the notion of freedom set forth above. Justice, on the other hand, is understood in opposition to the idea of private property and free competition, since these principles represent the foundations of political and economic liberalism. Since the Xiaoping reforms, the idea of social justice is interpreted as the progressive elimination of exploitation and social polarization. It is not for this brief essay to analyze the effective realization of such values, since this objective requires extensive and documented research that would probably face a shortage of sources and data.

Finally, at the individual level, this idea of debt to society is reinforced again, through patriotism and professional dedication. While the first value facilitates the application of the law promotes identification with national history and culture, the second favors labor productivity. To this is added the third value of this level, which is integrity by providing business ethics and allowing long-term alliances and projects, which is reinforced by the fourth value of friendship, which provides a solid social glue. Interactions between Chinese citizens as well as abroad. The latter is reflected in a strong diplomatic and para-diplomatic strategy where stable and lasting ties are created through social encounters that often exceed the formality to become legitimate forms of interaction based on mutual trust and respect. Everyone who has had the chance to visit China with a local host knows the benevolence of their hospitality and this counts for Elon Musk as well as for an ordinary person such as who writes these lines.

Conclusions

The good moment through which the Chinese economy passes, responds in large part to a cultural and normative substrate that in some cases derives from its millenary history, as is the case of the concept of harmony, and in others of its political and economic transformations of the last century related mainly to the Marxist component of its current political regime. The idea of harmony brings together much of the other values that are promoted at the national, social and individual levels, such as a concept of freedom restricted and subject to the rule of law, an idea of civilization understood as a series of social principles and norms that guarantee an adequate coexistence; or an idea of patriotism in which individuals overlap the collective good over the personal. Harmony also plays a crucial role in China's international politics, in which an active strategy of regional integration is promoted through mutually agreed relations within the framework of mutual benefit and learning.

In addition, the values prioritized and promoted by the government ensure prosperity based on the idea of a strong and solid economy that seeks greater access of the population to goods and services, for which values such as professional dedication and integrity are reinforced and friendship at the individual level so that the country's productivity is anchored in an efficient and disciplined work force.

Even so, in China there remain important challenges and critical knots related mainly to its democratic institutionality, development gaps in urban and rural areas, persistent inequality in the distribution of wealth and worrying environmental problems such as air pollution in large cities

Bibliography

Gao, J.; Jun, B.; Pentland, A.; Zhou, T.; and Hidalgo, C. (2017). Collective learning in China’s regional economic development. ArXiv.

Graeber, D. (2001). Toward an anthropological Theory of Value. The false coin of our own dreams.Palgrave Mcmillan. USA.

Hausmann, R.; Hidalgo, C.; Bustos, S.; Coscia, M.; Chung, S.; Jimenez, J.; Simoes, A.; and Yildirim, M. (2007). The Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping paths to prosperity.

Han, Zhen and Zhang, Weiwen (2018). China’s values. China social sciences press.

Johnson, C. (2016). President Xi Jinping’s “Belt and Road” Initiative. A practical assessment of the Chinese Communist Party’s roadmap for China’s global resurgence. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Pickety, T. (2013). El capital en el siglo XXI. Fondo de Cultura Económica. 2014, Chile.

Robbins, J. and Sommerschuh (2016). Values. University of Cambridge. England.

Sinha, Kunal (2008). China’s creative imperative. How creativity is transforming society and business in China. John Wiley and sons. Singapore.

World Bank (2018). Belt and Road Initiative. USA. The World Bank: Recuperado de: https://www.worldbank.org

Observatory of Economic Complexity (2017). China. Recuperado de: https://oec.world